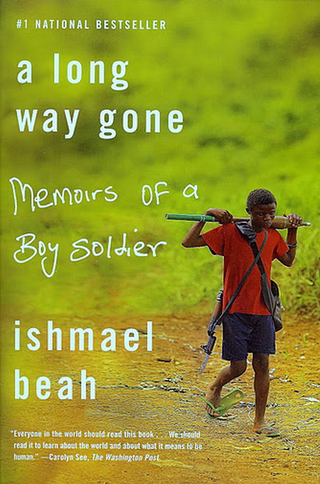

The photo on the cover—a boy on a dirt trail, hair uncombed, mortar cartridge behind his neck, and a gun with a bayonet hanging from his shoulders drew me to Ishmael Beah’s book. The green flip-flop on his right foot, useless and slanting in the wrong direction, a testament of happier times, sealed my fate. Reading the blurb was a formality as was thumbing Steve Job’s biography, which I had intended to buy in the first place.

I paid for the book and went home.

I read the book through one heart-wrenching weekend, stopping occasionally for the weight of sorrow to lift. It did not.

Beah tells his story, in my view, without an agenda or an axe to grind. It is as though he says, “This is my story. Jump to conclusions if you want. Ask questions if you care.” He narrates about his experience as a boy soldier in Sierra Leone, a boy flung into the throes of a war that consumes his family.

His memory is photographic, capturing detail in a way that helps you journey with him. The picture of him wandering in the forest haunts me still.

I walked for two days straight without sleeping. I stopped only at streams to drink water. I felt as if somebody was after me. Often, my shadow would scare me and cause me to run for miles. Everything felt awkwardly brutal. Even the air seemed to want to attack me and break my neck. I knew I was hungry, but I didn’t have the appetite to eat or the strength to find food. I had passed through burnt villages where dead bodies of men, women, and children of all ages were scattered like leaves on the ground after a storm. Their eyes still showed fear, as if death hadn’t freed them from the madness that continued to unfold. I had seen heads cut off by machetes, smashed by cement bricks, and rivers filled with so much blood that the water had ceased flowing. Each time my mind replayed these scenes, I increased my pace. Sometimes I closed my eyes hard to avoid thinking, but the eye of my mind refused to be closed and continued to plague me with images. My body twitched with fear, and I became dizzy. I could see the leaves on the trees swaying, but I couldn’t feel the wind.1

Reading this book almost upended my theology. Why do bad things happen to innocent people? If God is real and good, why doesn’t he stop it? What about ethnic cleansing and genocide in the Bible?

I have not found intellectually satisfying answers. I do not need them to believe, I only need them for debate.

After I closed the book, it took many days for sadness to leave me.

Is war like the Terminator movie? Does the good guy leave the epic fighting scene—usually a dark warehouse with chainsaws, spikes, naked wires, and bottles—limping into the light with the beautiful woman he rescued clinging to his arm, while we cheer and wait for them to kiss?

No.

I recall a scene from Machine Gun Preacher, where an orphan boy tells his story to Sam Childers, which unlocks my tears afresh.

I remember my parents in my sleep. My father was big like you. They shot him. The rebels told me, “If I do not kill my mother, they would shoot my brother and me.” And so, I killed my mother. If we allow ourselves to be full of hate, then they’ve won. We must not let them take our hearts2.

War leaves casualties as J.P. Clark describes in his poem, The Casualties3 (selected lines below).

The casualties are not only those who are dead;

They are well out of it.

The casualties are not only those who are wounded,

Though they await burial by instalment.

The casualties are not only those who started

A fire and now cannot put it out. Thousands

Are burning that had no say in the matter.

The casualties are many, and a good number well

Outside the scenes of ravage and wreck;

They are the wandering minstrels who, beating on

The drums of the human heart, draw the world

Into a dance with rites it does not know

We fall,

All casualties of the war

Because we cannot hear each other speak,

Because eyes have ceased to see the face from the crowd,

Because whether we know or

Do not know the extent of wrong on all sides

We are characters now other than before

The war began,

I have many questions, fewer answers, but I am at peace in the world as long as I do not let them take my heart.

©Timi Yeseibo 2014

1. Ishmael Beah, A Long way Gone, Memoirs of a Boy Soldier (New York: Sarah Crichton Books/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), 49.

http://www.alongwaygone.com

2. Machine Gun Preacher Movie.

http://www.machinegunpreacher.org/

3. J.P. Clark, The Casualties, Poems of Black Africa, ed. Soyinka Wole (London: Heinemann/AWS, 1975), 112.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Timi Yeseibo and livelytwist.wordpress.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.